Auditory Devotion

Sounds of the Past

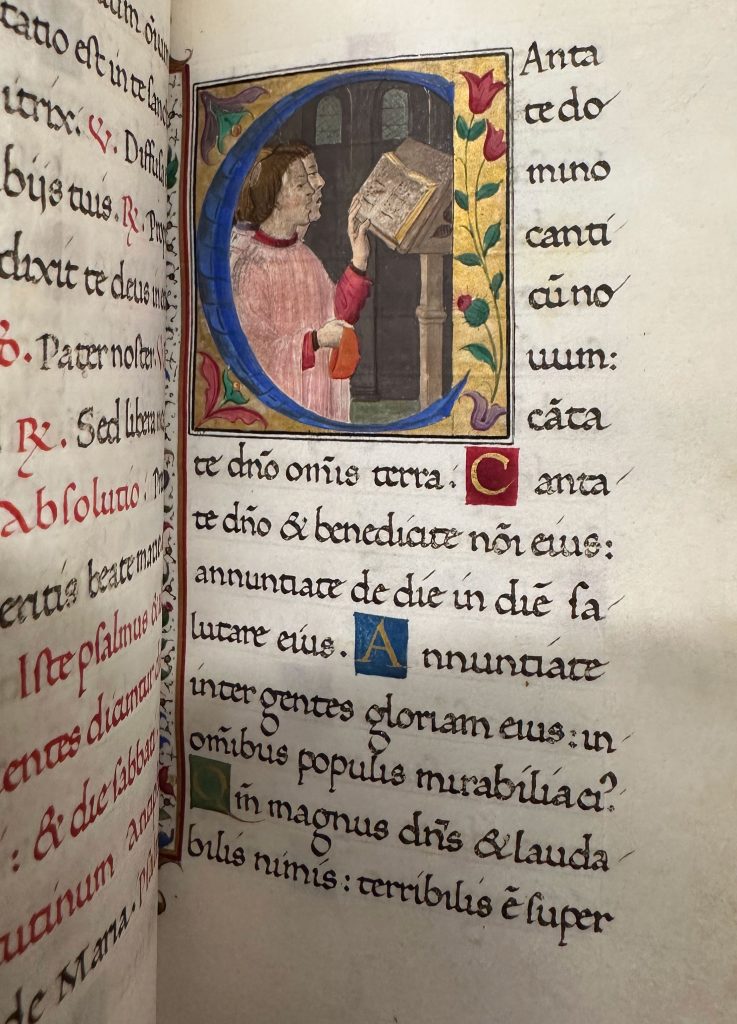

Music can evoke feelings of comfort or awe; it can bring people together and strengthen a sense of community. The exact origins of using song and sound in devotional practice is unknown, yet we know it far predates the Christian Church. The role auditory worship played in medieval Christian religion should not be overlooked. To speak and sing the words of these sacred texts was to be spiritually connected to God in an almost tangible way.

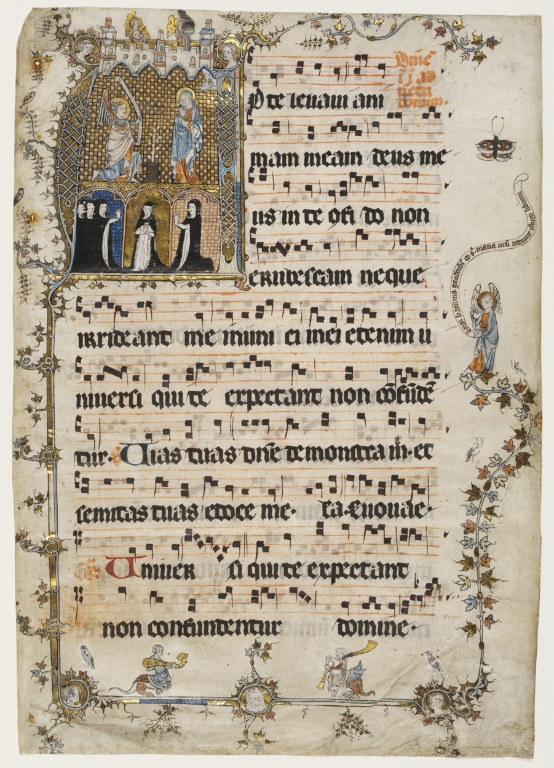

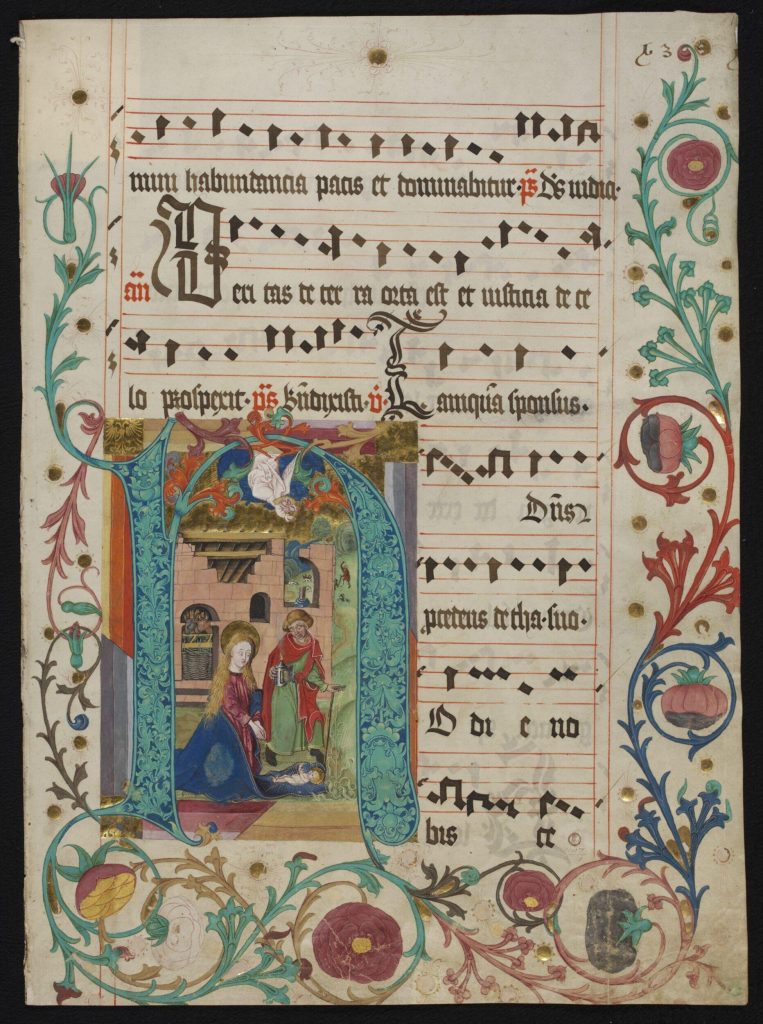

Auditory devotion can be seen in the fragments of medieval manuscripts that were cut and transformed by nineteenth-century collectors. A high proportion of cuttings came from choir books: large manuscripts meant to be read by the whole choir. This is because the size of such books – up to three-feet (one metre) wide when open - meant there was more space for decoration. The music in these choir books was written in different forms of plainsong, a chant that was normally sung a cappella (or unaccompanied) by monks and nuns, and was popular in the medieval church.

Graduals, of which there are examples dating back to the ninth century, contain the music and text sung during religious services, specifically the Mass, throughout the year. Antiphonaries (or Antiphonals) contain the music and text sung during the celebration of the Divine Office, a cycle of prayers recited at regular, prescribed hours of each day, as first codified in the sixth century. The book of Psalms in the Bible comprises sacred hymns or verse, which, traditionally sung as part of the liturgy, also encompass an important part of Christian worship. The Psalms were collected in Psalters to be sung by choirs, while the seven Penitential Psalms became a standard feature of Books of Hours.