Physical Devotion

Tactile Traces of History

Medieval illuminated manuscript cuttings are not only fragments of pigment and vellum, they are tactile chronicles of human devotion shaped by centuries of touch. Examining these artefacts allows us to trace the fingerprints of history, revealing how both medieval worshippers and nineteenth-century collectors engaged with manuscripts as objects of spiritual and sensory power.

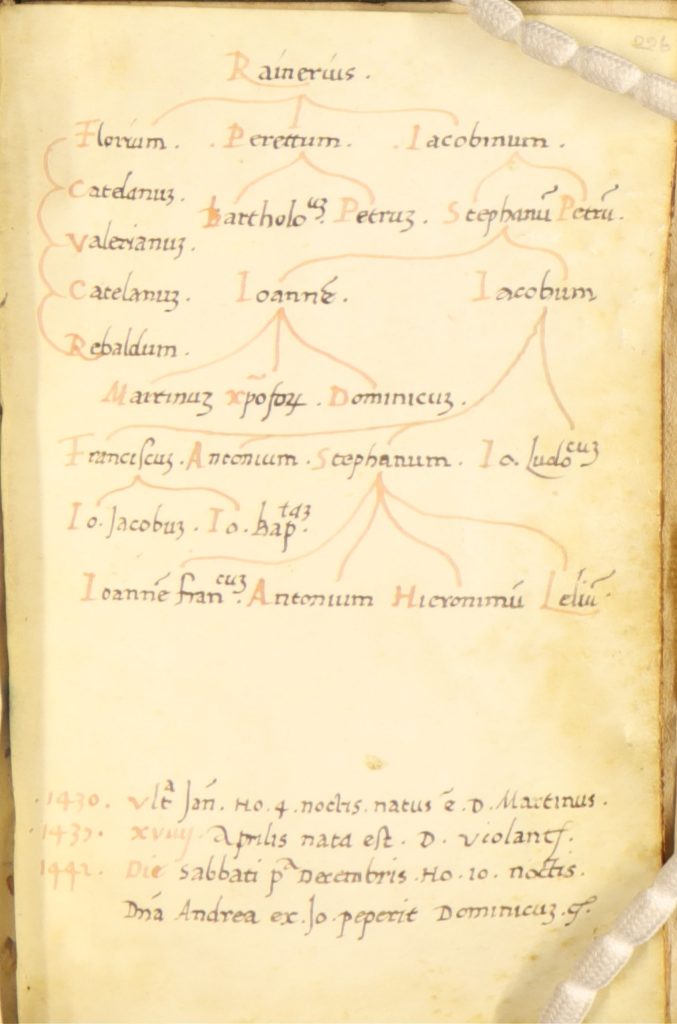

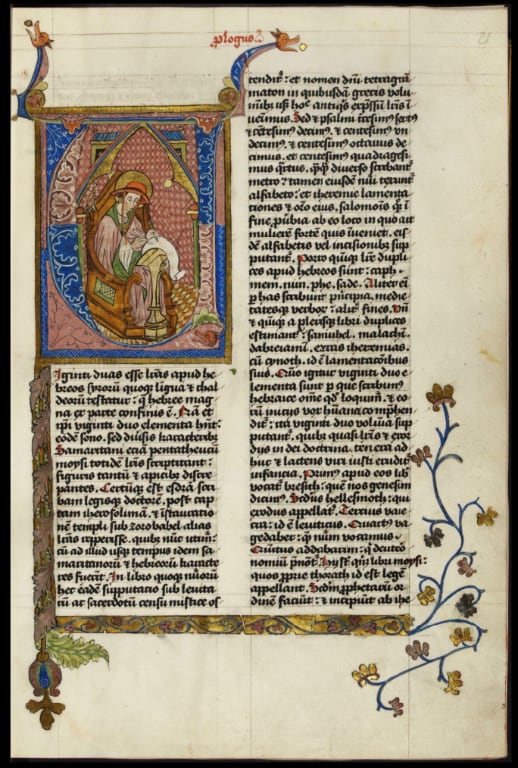

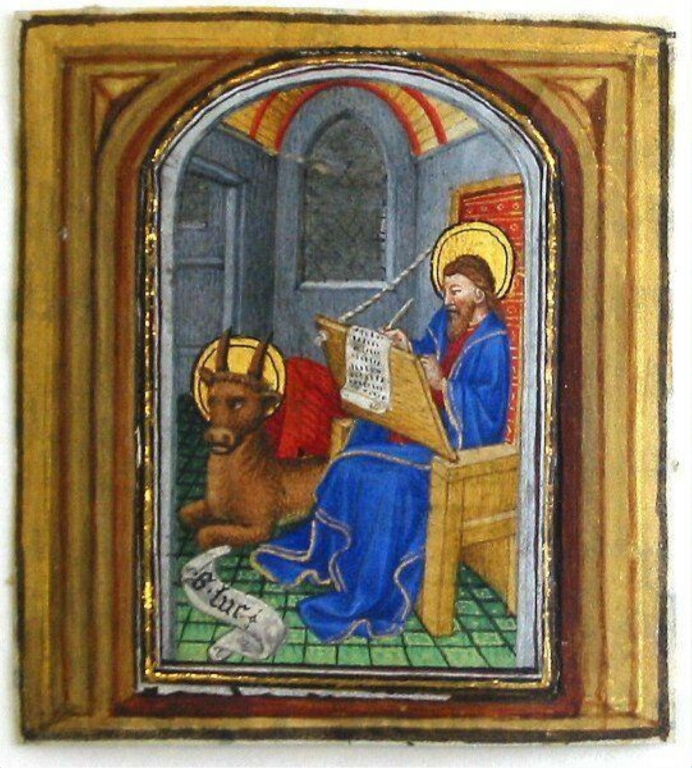

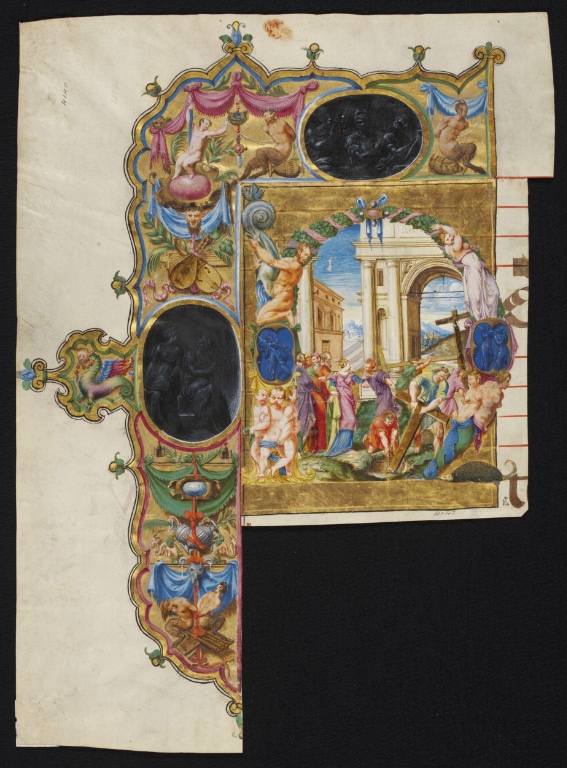

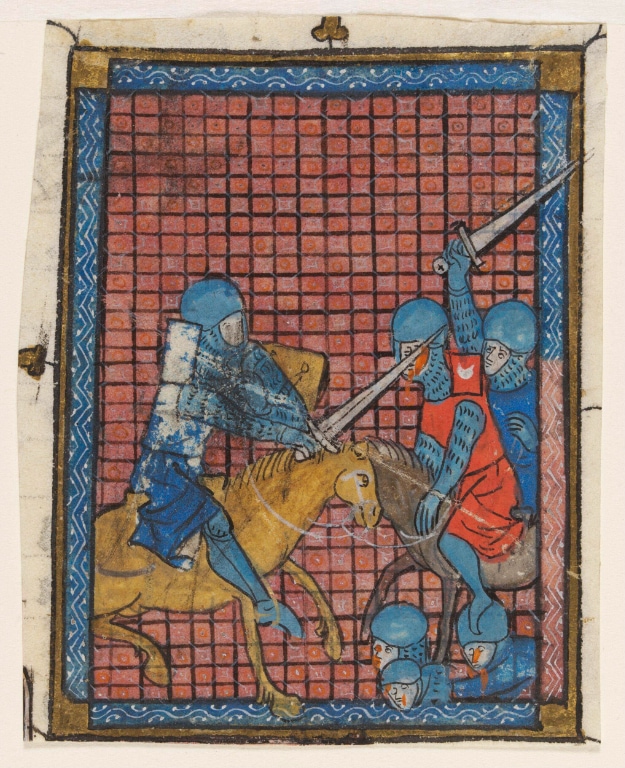

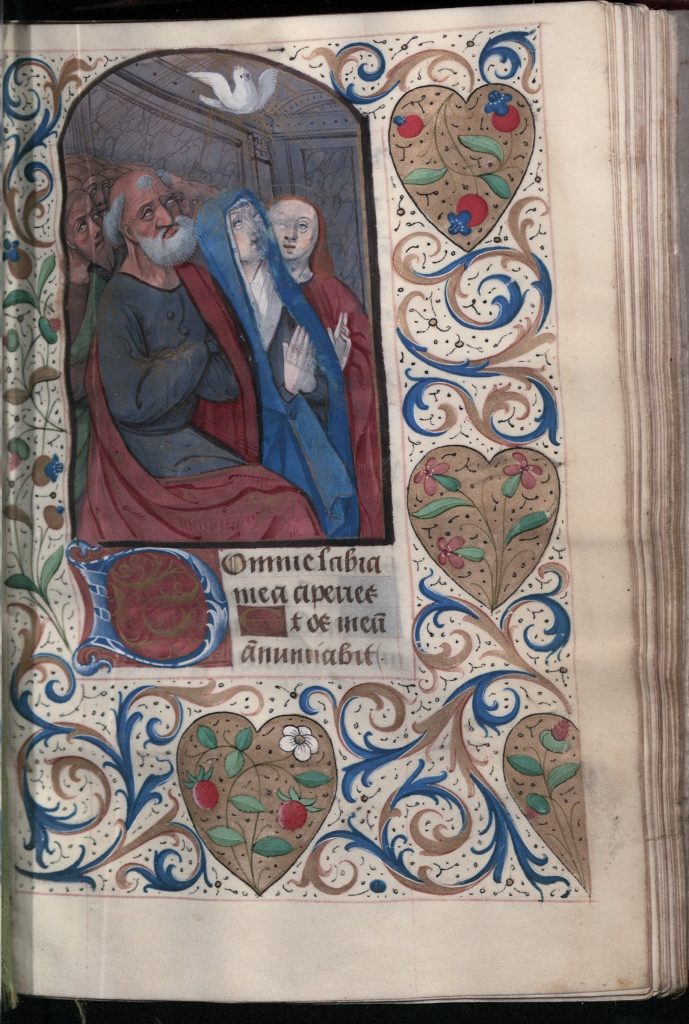

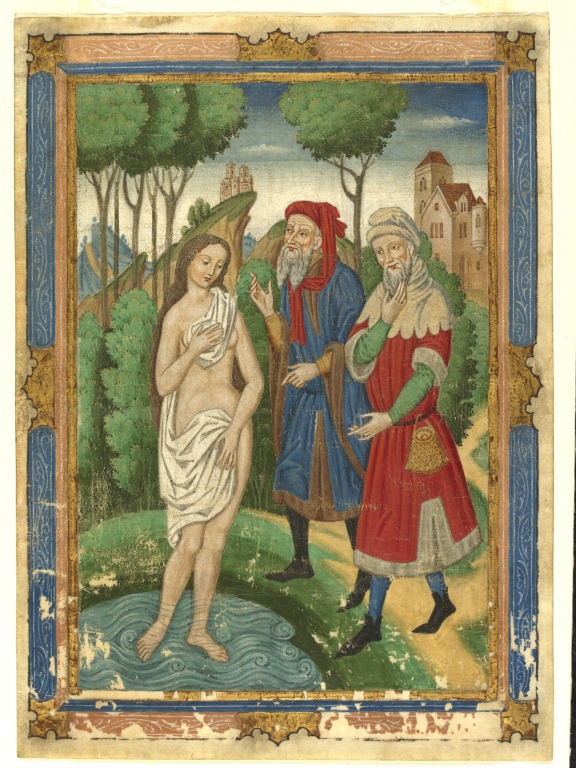

In the Christian middle ages that produced them, illuminated manuscripts were not simply read, they were experienced. Devotion was a physical practice. Worshippers kissed painted saints, tracing them with their fingertips, annotated sacred initials and stitched in fabric curtains to protect their beautiful illustrations. All of these acts left traces of physical interactions, visible through smudges, creases and needle holes. Marginal annotations, genealogical charts, seasonal calendars and handwritten prayers further personalised these volumes, embedding them into daily life. The wear upon these manuscripts shows traces of human interaction and devotion.

Scenes within illuminated manuscripts often reveal how medieval people physically showed acts of devotion. Kneeling and praying was conventional practice and so repeatedly represented in the manuscripts. Similarly, nineteenth-century attitudes to manuscript cuttings show a very different approach to the physical reinterpretation of devotion. Where medieval worshippers cherished manuscripts as sacred objects, these later collectors took them apart, cutting out illuminated initials and miniatures. Often these ritualistic methods were to suit their own aesthetic principles, as acts of devotion to the artistry, or as a devotion to the preservation of sacred images which, in these instances, if not cut and kept may not have existed today.