Animals and Creatures in Medieval Manuscript Marginalia

Medieval manuscript marginalia have long fascinated scholars and the wider public alike. Far from being just decoration, these marginal illustrations offer critical insight into medieval thought, visual culture, and symbolic imagination. Among the most captivating subjects that appear in the margins are animals and hybrid creatures, ranging from the holy to the grotesque. Their presence can be playful, unsettling, or deeply symbolic. This essay explores the roles and representations of animals and creatures in manuscript marginalia, particularly through three interpretive lenses: the curious, and incongruous; hybrids or grotesques; and the familiar, or benign.

Introductory Video

Video Transcript

Margins of Meaning: Whimsy and Wonder in Medieval Manuscripts

By Ruth Warhurst

Have you ever noticed the weird and whimsical figures and decorations around the edges of medieval manuscript pages and wondered why they are there?

These are known as marginalia, and though they often seem bizarre, they are filled with meaning. They offered medieval readers another way to engage with the text. In a time when books were handmade, illuminated with decorative illustrations and designs, and deeply valued, even the margins became meaningful spaces for reflection and imagination

What makes the margins of these manuscripts so fascinating?

Is it their beauty? or their strangeness? Or even their ability to disrupt and expand the meaning of the text?

Artists sometimes used the edges of the page to respond to what was written, or to veer off in entirely different directions. The decoration could challenge, echo, or playfully distort religious themes, allowing readers to engage with these sacred texts in surprising ways.

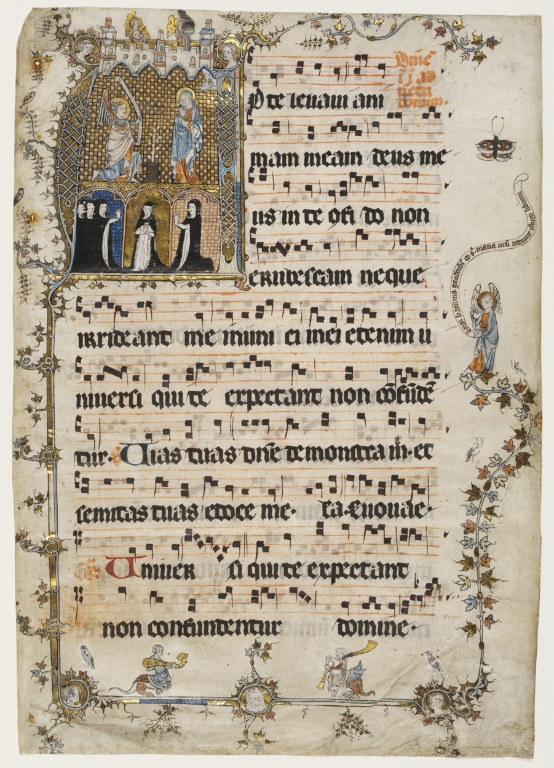

This page comes from an Antiphoner, which is a book filled with prayers and musical scores, made around 1350 in Cologne. It is part of the V&A’s collection, and its history reveals something especially remarkable: it was created by Sister Loppa de Speculo, who worked as both the scribe and the illuminator. This means she was responsible for both the writing and the decoration, offering us a rare glimpse into the skilled artistic work carried out by women in religious communities.

The page immediately captivates the eye. Three sides are bordered with intricate patterns in gold and blue, a design that would have been costly to produce. The edges shimmer with gilding, showing just how precious this book was to its makers and its readers.

Mirrored at the top and bottom of the page, two small dragons sit, facing one another. Dragons had lots of meanings in the medieval period – they could represent spiritual evil, but were also symbols of wisdom and protection. These dragons don’t look especially fierce, menacing or wise. In fact, they’re a little funny, even sweet. With their curling tails and gentle expressions, they feel more like characters in conversation than symbols of fear.

In the bottom right corner, a long-necked bird perches delicately on a winding vine. It’s drawn with careful detail and just enough exaggeration to make it delightful. Birds like this often appeared in devotional manuscripts, sometimes as symbols of the soul, sometimes simply as expressions of beauty and imagination.

This mix of whimsical creatures, precious materials, and spiritual music all on one page shows us how layered and expressive these books could be. The manuscript was a sacred object, but also a work of art.

Marginalia were more than decoration. They were a vital part of the manuscript, capable of unsettling, amusing, and provoking thought, as well as supporting the message of the text. In working on the Barber’s online exhibition, Fragments of Devotion, I’ve come to see that the edges of the page often hold the most surprising insights. The corners offer a glimpse into a world where art, devotion, and imagination were never far apart.

Margins as Meaningful Space

Before examining individual categories, it is important to consider the significance of marginal spaces in medieval manuscripts. Margins were exciting spaces where illuminators could expand, reflect upon, or even gently mock the central text. As Michael Camille argued in Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, marginalia did not just decorate. Instead, the marginal art ‘disrupted and questioned the authority of the page […] Things written or drawn in the margins add an extra dimension, a supplement, that can gloss, parody, modernise and problematise the text’s authority while never totally undermining it.’ Camille further noted that ‘The efflorescence of marginal art in the thirteenth century must be linked to changing reading patterns, rising literacy and the increasing use of scribal records as forms of social control. ’ In this light, animals and hybrid creatures were not simply amusing embellishments. They were part of a wider cultural response to how texts were read, interpreted, and visually engaged with. The margins became places of experimentation, where imagination and commentary could thrive.

The Curious

Marginal animals and creatures rarely have straightforward interpretations and can be fascinating through their unexpected combinations. A compelling example is found in Fig.1, a leaf from a Gradual. The large historiated initial ‘A’ illustrates the Annunciation, with the Angel Gabriel greeting the Virgin Mary. In the outer margin, another angel holds a scroll inscribed with the names ‘Katerina of Gouda’ and ‘Maria Ursi’, two nuns who gifted the book.

Surrounding the sacred scene are birds, a butterfly, and a cast of grotesque figures. This leaf reflects a broader trend that emerged in the final decades of the thirteenth century, where text frames were increasingly filled with regiments of grotesques.

These often took the form of half-human, half-beast figures, mingling with naturalistic animals and dragons. While some of these grotesques may relate symbolically to the text, more often they appear to be engaged in playful activity. In this choir book, made for a community of Dominican nuns, female grotesques playing musical instruments appear directly beneath the praying figures of the nuns. The contrast can appear amusing. This kind of illumination exemplifies the rich interpretive possibilities of marginalia. As Camille observed, the ‘dream-like logic of such images resists rational explanation but encourages audiences to think about what they are seeing and reading.’

Grotesques

While some images are playful, others evoke unease through their hybrid or grotesque nature. Fig.2 presents an unsettling figure: a creature with the head of a jester and the body of a dog. This fusion of human and animal elements is a classic example of the grotesque. Jesters were already figures of humour in the medieval imagination, also pointing up the absurdity of life. Placing a jester’s head on an animal body intensifies the sense of disorder, inviting reflection on the nature of identity, all inside a small initial.

Fig.3 offers a further example of strangeness. This leaf comes from an Antiphonal, produced in 1350 by Sister Loppa de Speculo who was both the illuminator and the scribe. In the margins of this manuscript, we find dragons and birds. Dragons, often symbolic of evil and chaos, contrasted with birds, traditionally associated with the soul or divine inspiration. There was an established tradition of showing both real animals and mythic icons alongside each other on the page, sometimes with meaning, sometimes with apparent whimsy. Also in the margins, though venerating the main image, is a nun, the Abbess Heylwigis von Beechoven, and the meaning of the imagery perhaps relates to her life and the need to focus on the divine, avoiding earthly temptations.

The Familiar

Not all animals in manuscript art are grotesque or fantastical. Many appear in familiar, comforting roles. Birds, dogs, and rabbits are often shown engaging with plants, playfully interacting, or resting in the decorative borders. These images reflect a medieval worldview that saw nature as a meaningful and an integrated part of existence. Fig.1 features a bird and butterfly, created with care and delicacy.

Although less attention-grabbing than hybrid angels or dragons, these gentle creatures lend a sense of quiet harmony to the leaf. Butterflies often symbolise resurrection, while birds often signify the soul or messages from the divine.

A particularly important example is Fig.4, which is not marginalia but a central illumination. Likely from a Book of Hours, it shows Saint Luke and his symbol, the ox. The ox represents strength, sacrifice, and priestly duty. Unlike the marginal grotesques, this creature is placed at the heart of the manuscript’s sacred function. Its role is not decorative or humorous but deeply symbolic, underscoring the theological foundations of the text. These friendly animals, whether in the margins or the centre, reinforce the idea that the animal world was both familiar and spiritually significant to medieval readers.

From Luke’s ox to tiny butterflies in the margins, animals in medieval manuscripts demonstrate the variety of medieval visual culture. They remind us that medieval reading was not solely about absorbing religious texts, but also about experiencing wonder, questioning norms, and imagining new possibilities, sometimes just at the edge of the page.

Ruth Warhurst

Image List

Fig. 1 Leaf from a Dominican Gradual with an Historiated Initial ‘A’ showing the Annunciation, The Netherlands, about 1330. Pigments, gilding and ink on parchment. Victoria and Albert Museum (No. 8992) (see Manuscript Cutting: Leaf from a Gradual showing The Annunciation)

Fig. 2 Historiated Initial ‘S’ from a Choir Book showing the Birth of the Virgin, Netherlands, about 1350. Ink and pigments on parchment, 98 x 111 mm. Victoria and Albert Museum (No. 4019)

Fig. 3 Loppa de Speculo, Leaf from an Antiphoner from the Franciscan Convent of Saint Klara, Cologne with an Historiated Initial ‘D; showing the Pentecost, Cologne, about 1350. Gold, ink and pigments on parchment. Victoria and Albert Museum (No. 89971) (see Manuscript Cutting: Leaf from an Antiphoner from the Franciscan Convent of Saint Klara, Cologne with an Illuminated Initial ‘D’)

Fig. 4 Miniature of Saint Luke and his Symbol, probably from a Book of Hours, Paris, 1420s. Ink, pigments and gold on parchment. Victoria and Albert Museum (No. 9019A/1) (see Manuscript Cutting: Illumination from a Book of Hours showing Saint Luke)

Further Reading

Camille, Michael, Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, London, 1992

Sandler, Lucy Freeman, ‘The Study of Marginal Imagery: Past, Present, and Future’, Gesta, 36/1, 1997, pp. 5–15

Wilson, Matthew, ‘Butterflies: The ultimate icon of our fragility’ (2021), BBC Culture

‘The Symbols of the Evangelists’ (2025), The Fitzwilliam Museum